Table of Contents

1. Introduction

We have seen in a previous post how we can estimate the homography matrix $H$ that characterizes the projective transform between two images. This matrix takes the form:

$$ \begin{equation} H= K \cdot \left[\; R\;\; | \;\;\ T\;\;\right ] \end{equation} $$

where:

- $R$ is a rotation matrix that defines the camera orientation. It is fully characterized by the rotation angles $[\theta_x, \theta_y, \theta_z]$ around the $x$, $y$ and $z$ axes, respectively.

- $T$ is a translation vector that defines the camera location. It is given by the coordinates $[t_x, t_y, t_z]$.

- $K$ is the intrinsic matrix, which contains the camera parameters. It is given by: $$ \begin{equation} K=\begin{bmatrix} f_x & s & c_x \\ 0 & f_y & c_y \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \end{equation} $$

The figure below illustrates the capture of an image. You can tweak the sliders to change the camera parameters and see how the image changes.

(a) 3D World View

(b) Camera View

In this article, we will focus on the camera calibration problem, which consists of retrieving the intrinsic matrix $K$of the camera.

2. Conics

Conics play a key role in the process of calibrating the camera, so let us start by introducing some of their properties.

We can express conics in homogeneous coordinates as the set of points $x$ that satisfy the equation:

$$ \begin{equation} x^T\cdot C\cdot x=0 \end{equation} $$

where $C$ is a symmetric matrix. Depending on whether it has full rank or not, the conic is non degenerate or degenerate.

As we saw in our previous post, a conic gets mapped to another conic under a projective transformation:

$$ \begin{equation} C’ = H^{-T}\cdot C\cdot H^{-1} \end{equation} $$

where $H$ is the homography matrix. In this section, we will introduce some conic properties that will be useful for understanding the camera calibration problem.

2.1. Tangency

The line $l$ tangent to a conic at a point $x$ is defined by the equation:

$$ \begin{equation} l=C\cdot x \end{equation} $$

In order to prove it, we need to verify that the point $x$:

- Lies on the line. That is true if $l^T\cdot x=0$: $$ \begin{equation} l^T\cdot x = (C\cdot x)^T\cdot x = x^T\cdot C^T\cdot x = x^T\cdot C\cdot x = 0 \end{equation} $$

- Is the only point of intersection between the conic and the line. We can prove its uniqueness by contradiction. Suppose there is another point $y$ on the line ($l=C\cdot y$) that lies on the conic $y^T\cdot C\cdot y = 0$. We can then take a linear combination $r = x + \alpha y$. For every $\alpha$, the point $r$ lies on the line: $$ \begin{equation} l^T\cdot r = l^T\cdot x + \alpha l^T\cdot y = 0 \end{equation} $$ But it also happens to lie on the conic: $$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} r^T\cdot C\cdot r & = (x + \alpha y)^T\cdot C\cdot (x + \alpha y) \\ & = x^T\cdot C\cdot x + 2\alpha x^T\cdot C\cdot y + \alpha^2 y^T\cdot C\cdot y \\ & = x^T\cdot C\cdot x + 2\alpha l^T\cdot y + \alpha^2 y^T\cdot C\cdot y \\ & = 0 \end{split} \end{equation} $$

which would imply the whole line intersects with the conic, which is unfeasible for non-degenerate conics. Therefore, the point $x$ is the only point of intersection between the line and the conic.

Tangency is preserved under the projective transformation. That is, if $l$ is tangent to the conic $C$ at point $x$, then $l’$ is tangent to the conic $C’$ at point $x’$. Recall that we can project each item under the homography matrix $H$ by:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} x’ & = H\cdot x \\ l’ & = H^{-T}\cdot l \\ C’ & = H^{-T}\cdot C\cdot H^{-1} \end{split} \end{equation} $$

In order for $l’$ to be tangent to $C’$ at $x’$, it must satisfy $l’^T=C’\cdot x’$:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} C’\cdot x’ & = H^{-T}\cdot C\cdot H^{-1}\cdot H\cdot x \\ & = H^{-T}\cdot C\cdot x \\ & = H^{-T}\cdot l \\ &= l' \end{split} \end{equation} $$

2.2. Duality

There is a duality between lines and points in the projective space that shows up everywhere. We can observe it in the way points/lines relate to conics.

As we have seen in the previous section, for every point in the conic that satisfy $x^T\cdot C\cdot x = 0$, there is a unique tangent line $l=C\cdot x$ that passes through it. If C has full rank, we can invert it so $x=C^{-1}\cdot l$, which leads to

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} x^T\cdot C\cdot x &= x^T\cdot C^T \cdot C^{-T}\cdot C\cdot x \\ &= (C\cdot x)^T\cdot C^{-T}\cdot C\cdot x \\ &= l^T\cdot C^{-T}\cdot l \\ &= 0 \end{split} \end{equation} $$

In the general case, it can be proven that the dual conic is given by the adjoint matrix $C^*$, up to scale:

$$ \begin{equation} l^T\cdot C^*\cdot l = 0 \end{equation} $$

which can be interpreted as the conic built from the set of lines tangent to it. This also implies given a line $l$ tangent to a conic $C*$, the point $x$ where it intersects the conic satisfies

$$ \begin{equation} x = C^*\cdot l \end{equation} $$

To simplify the notation, we will denote point conics as $C$ and line conics as $D$. The projection $D’$ of a line conic $D$ under a homography matrix $H$ satisfies:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} l’^T\cdot D’\cdot l’ &= l^T\cdot H^{-1}\cdot D’\cdot H^{-T}\cdot l \\ &= l^T\cdot D\cdot l \\ &= 0 \end{split} \end{equation} $$

which implies

$$ \begin{equation} D’ = H\cdot D\cdot H^T \end{equation} $$

2.3. Pole-polar relationship

The equation $l=C\cdot x$ determines the tangent line whenever $x$ lies on the conic $C$. However, it defines a broader relationship between lines and points with respect to the conic. This relationship is known as the pole-polar relationship.

Assuming the point $x$ lies outside the conic, we can build two lines $l_1$ and $l_2$ passing through it that are tangent to the conic at $x_1$ and $x_2$, respectively. We know from the previous section, those lines are given by:

$$ \begin{equation} l_i = C\cdot x_i \end{equation} $$

Furthermore, the intersection point ($x$ by construction) between two lines in homogenous coordinates is given by the cross product:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} x &= l_1\times l_2 \\ &= (C\cdot x_1) \times (C\cdot x_2) \end{split} \end{equation} $$

From the properties of the cross product, this simplifies to: $$ \begin{equation} x = (C^*)^T\cdot (x_1\times x_2) \end{equation} $$

where $C^*$ is the adjoint matrix, whose transpose is the cofactor matrix. For conics, it is a symmetric matrix. Notice that the cross-product of two points in homogenous coordinates is the line passing through them, so the previous equation becomes:

$$ \begin{equation} x = C^*\cdot l \end{equation} $$

Therefore, the polar $l=C^*\cdot x$ of a point $x$ with respect to a conic $C$ intersects the conic at two points. The two lines tangent to the conic at these points intersect at the pole $x$.

The polar-pole relationship is also valid when a point lies inside the conic, as illustrated below

The pole-polar relationship is preserved under projective transformations. If $l=C\cdot x$ is the polar of $x$ with respect to the conic $C$, then:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} l’ &= H^{-T}\cdot l \\ &= H^{-T}\cdot C\cdot x \\ &= H^{-T}\cdot H^{T} \cdot C \cdot H \cdot H^{-1}\cdot x’ \\ &= C’\cdot x' \end{split} \end{equation} $$

so $l’$ is the polar of $x’$ with respect to the conic $C’$.

2.4. Conjugacy

Two points $x$ and $y$ are said to be conjugate with respect to a conic $C$ if one lies on the polar of the other. For instance, if $x$ lies on the polar $l=C\cdot y$, then:

$$ \begin{equation} l^T\cdot x = 0 \Rightarrow y^T\cdot C\cdot x = 0 \end{equation} $$

This relationship is symmetric, so if $x$ lies on the polar of $y$, then $y$ lies on the polar of $x$.

Due to duality, thereis an analogous concept for lines. Two lines $l$ and $m$ are said to be conjugate with respect to a conic $C$ if each passes through the pole of the other. This implies, the following is sastisfied:

$$ \begin{equation} l^T\cdot C^*\cdot m = 0 \end{equation} $$

Importantly, the operation $\mathbf{l^T\cdot C^*\cdot m}$ is invariant under projective transformations:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} l’^T\cdot C’^*\cdot m’ & = (H^{-T}\cdot l)^T\cdot (H^{-T}\cdot C\cdot H^{-1})^T\cdot H^{-T}\cdot m \\ & = l^T\cdot H^{-1}\cdot H\cdot C\cdot H^T\cdot H^{-T}\cdot m \\ & = l^T\cdot C\cdot m \end{split} \end{equation} $$

which obviously implies conjugacy is also preserved under projective transformations.

3. Undoing the projective distortion

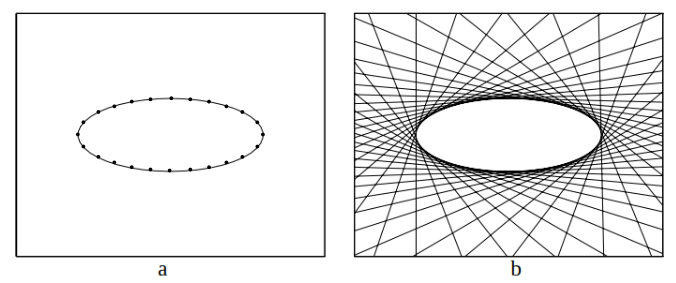

One of the most important concepts in Euclidean geometry is the angle between two lines. However, the projective transformation does not preserve angles, preventing us from measuring them directly through the observed projections. This is illustrated below:

In this section, we will see how we can tackle this problem.

3.1. 2D projective space

We will start by focusing on the 2D projective space, which is a generalization of the Euclidean 2D space. Two 2D planes are related by a projective transformation, which can be represented by an invertible 3x3 matrix homography matrix $H$.

3.1.1. Angles between rays

Say we want to measure the angle between two lines $l=[l_1, l_2, l_3]^T$ and $m=[m_1, m_2, m_3]^T$ in the Euclidean plane. We know that the angle between two lines is given by the equation:

$$ \begin{equation} \cos(\theta) = \frac{l_1m_1 + l_2m_2}{\sqrt{(l_1^2 + l_2^2)(m_1^2 + m_2^2)}} \end{equation} $$

where the normal vectors of the lines are $n_l=[l_1, l_2]^T$ and $n_m=[m_1, m_2]^T$.

Can we express the angle between the two lines $l$ and $m$ in terms of the observed projections $l’$ and $m’$? We know that the projections are related by the homography matrix $H$:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} l’ & = H^{-T}\cdot l \\ m’ & = H^{-T}\cdot m \end{split} \end{equation} $$

As discussed before, if we were to compute the angle from lines $l’$ and $m’$ using the previous equation, we would get a different result.

But look carefully at the equation. Notice we have not used the product of the line vectors $l$ and $m$ at all. Instead, we have used the product of the normal vectors $n_l$ and $n_m$. Can you think of any way to manipulate the equation so that we can express the angle in terms of $l$ and $m$?

Maybe the following matrix will help you:

$$ \begin{equation} D=\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \end{equation} $$

We can now rewrite the equation as:

$$ \begin{equation} \cos(\theta) = \frac{l^T\cdot D\cdot m}{\sqrt{(l^T\cdot D\cdot l)(m^T\cdot D\cdot m)}} \end{equation} $$

Leveraging the invariance of the product $l^T\cdot D\cdot m$ under projective transformations, we can measure the angle by:

$$ \begin{equation} \cos(\theta) = \frac{l’^T\cdot D’\cdot m’}{\sqrt{(l’^T\cdot D\cdot l’)(m’^T\cdot D\cdot m’)}} \end{equation} $$

where $D’=H\cdot D\cdot H^T$. This implies we can measure the angle between two lines from their projections!

This result may seem trivial, what’s the big deal? If the homography matrix is known, you can just project back all observed lines to the Euclidean plane and measure the angle there. And that is absolutely true! But this derivation sets the stage for 3D case, where things are not as straightforward.

3.1.2. The line at infinity

Wait a second, so how do we interpret the matrix $D$? What does it represent? To answer these questions, we need to jump into the realm of infinity!

Although Euclidean 2D and 3D spaces are very useful for representing objects in the real world, they have some limitations. For instance, they do not include points at infinity, which are essential for the representation of parallel lines and planes. On the other hand, projective spaces are a more general representation of spaces that indeed include points at infinity.

A point $p_E=[x,y]^T$ in the Euclidean plane is represented as a 3D vector in homogeneous coordinates as:

$$ \begin{equation} p=[x, y, 1]^T \end{equation} $$

Any scaled version of this vector represents the same point in the Euclidean plane:

$$ \begin{equation} p = [\lambda x, \lambda y, \lambda]^T \end{equation} $$

So we can easily retrieve the Euclidean coordinates of a point by dividing the first two components by the third one:

$$ \begin{equation} p_E = \left[\frac{p_x}{p_z}, \frac{p_y}{p_z}\right]^T \end{equation} $$

This representation allows us to include points at infinity: $$ \begin{equation} p_{\infty} = [x, y, 0]^T \end{equation} $$

Notice that a line in the Euclidean plane is represented by the equation $ax+by+c=0$. In the projective space, the line is parametrised by the vector

$$ \begin{equation} l=[a, b, c]^T \end{equation} $$

and the point $p$ lies on the line if it satisfies:

$$ \begin{equation} l^T\cdot p=0 \end{equation} $$

As a result, the line at infinity is represented by the vector

$$ \begin{equation} l_{\infty}=[0, 0, 1]^T \end{equation} $$

3.1.3. The circular points

Say we have a circle, whose conic matrix is given by:

$$ \begin{equation} C=\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & k \end{bmatrix} \end{equation} $$

The circle grows larger as $k$ increases, so in the limit $k\rightarrow \infty$, it must be composed of points at the infinity line. We can characterize it by its dual conic $C^*_{\infty}$:

$$ \begin{equation} C^*_{\infty}=\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \end{equation} $$

which describes a degenerate conic, since it has rank 2. And this is precisely the matrix $D$. Points on it must satisfy

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} x_1^2 + x_2^2 = 0 \\ x_3 = 0 \end{split} \end{equation} $$

so a basis for the solution are the circular points $\{ \mathbf{I}, \mathbf{J} \}$ given by the vectors:

$$ \begin{equation} \mathbf{I}=\begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ i \\ 0 \end{bmatrix}, \mathbf{J}=\begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ -i \\ 0 \end{bmatrix} \end{equation} $$

The term “circular points” comes from the fact that all circles intersect with the infinity line at these points. Recall a circle is defined by the equation:

$$ \begin{equation} x_1^2 + x_2^2 + d x_1 x_3 + e x_2 x_3 + f x_3^2 = 0 \end{equation} $$

For a point in the circle to lie on the infinity line, it must satisfy $x_3=0$, so the equation simplifies to:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} x_1^2 + x_2^2 & = 0 \\ x_3 & = 0 \end{split} \end{equation} $$

which is exactly the same system!

At this point you may be wondering: what on earth are we doing? After all, this conic consists of imaginary points that lie at the infinity line, so it can not be observed. The important thing to notice is that it is a conic, and it can therefore be mapped under any projective transformation as any other conic.

For now, just think of it as a mathematical artifact that plays a key role in determining the angle between lines.

3.2. 3D projective space

Let us now focus on the 3D projective space, where a point $p_E=[x, y, z]^T$ in the Euclidean space is represented by a 4D vector in homogeneous coordinates as:

$$ \begin{equation} p=[x, y, z, 1]^T \end{equation} $$

3.2.1. The plane at infinity

Similarly to the 2D case, points at infinity take the form:

$$ \begin{equation} p_{\infty}=[x, y, z, 0]^T \end{equation} $$

The equation for a plane in the Euclidean space is given by $ax+by+cz+d=0$. We parametrize the plane by the vector:

$$ \begin{equation} \Pi=[a, b, c, d]^T \end{equation} $$

So a point $p$ lies on the plane if it satisfies:

$$ \begin{equation} \Pi^T\cdot p=0 \end{equation} $$

Points at infinity are represented by the vector:

$$ \begin{equation} p_{\infty}=[x, y, z, 0]^T \end{equation} $$

The plane at infinity must satisfy

$$ \begin{equation} \Pi_{\infty}^T\cdot p_{\infty}=0 \end{equation} $$

which leads to:

$$ \begin{equation} \Pi_{\infty}=[0, 0, 0, 1]^T \end{equation} $$

3.2.2. The absolute conic

We can follow a similar logic to the 2D case. Say we have a sphere, whose conic matrix is given by:

$$ \begin{equation} Q=\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & k \end{bmatrix} \end{equation} $$

As we increase $k$, the sphere grows larger, and in the limit $k\rightarrow \infty$ we get the absolute conic $\Omega_\infty$.

This conic must be composed of points at the infinity plane, so it can be described by two equations:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} x_1^2 + x_2^2 + x_3^2 & = 0 \\ x_4 & = 0 \end{split} \end{equation} $$

Even though this is a pretty abstract concept, we can make an interesting observation about the absolute conic: all circles intersect with the absolute conic at two points. This is because a circle lies in a plane, whose intersection with the infinity plane is a line. This line will in turn intersect with the absolute conic at precisely two points, the circular points!

3.2.3. Angles between rays

Say we have two rays in 3D whose direction vectors are $d=[d_x, d_y,d_z]^T$ and $e=[e_x,e_y,e_z]^T$. The angle between them is given by:

$$ \begin{equation} \cos(\theta) = \frac{d^T\cdot e}{\sqrt{(d^T\cdot d)(e^T\cdot e)}} \end{equation} $$

A ray with direction vector $d$ intersects the infinity plane at the point $p_d=[d_x, d_y, d_z, 0]^T$. Since the fourth component is zero, we can write the product with the absolute conic as:

$$ \begin{equation} p_d^T\cdot \Omega_{\infty}\cdot p_e = \begin{bmatrix} d_x & d_y & d_z \end{bmatrix} \cdot \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \cdot \begin{bmatrix} e_x \\ e_y \\ e_z \end{bmatrix} \end{equation} $$

So we can compute the angle between the rays from their intersection with the infinity plane by:

$$ \begin{equation} \cos(\theta) = \frac{p_d^T\cdot \Omega_{\infty}\cdot p_e}{\sqrt{(p_d^T\cdot \Omega_{\infty}\cdot p_d)(p_e^T\cdot \Omega_{\infty}\cdot p_e)}} \end{equation} $$

This may seem too abstract, we are dealing with points at infinity that can not be observed. But remember, the absolute conic is a conic, and it can be projected under any projective transformation as any other conic. We will see in a later section how this can be used to measure the angles between 3D rays passing through the camera center, from just their observed point projections.

For instance, notice that if two rays with direction $d_1$ and $d_2$ are orthogonal, their points of intersection with the infinity plane $\Pi_{\infty}$ will be conjugate points with respect to the absolute conic $\Omega_{\infty}$. And conjugacy is preserved under projective transformations!

Furthermore, say we have a plane $\Pi_1$. It intersects with the plane at infinity $\Pi_{\infty}$ at a line $l$. The ray normal to it does so at the point $d_1$. We can now take two planes $\Pi_2$ and $\Pi_3$ orthogonal to it, whose normal rays intersect with $\Pi_{\infty}$ at $d_2$ and $d_3$, respectively. Two important remarks:

- Since the $\Pi_2$ and $\Pi_3$ are orthogonal to $\Pi_1$, both $d_2$ and $d_3$ are conjugate points w.r.t. $\Omega_{\infty}$. Or equivalently, they must lie on the polar of $d_1$.

- Since the rays $d_2$ and $d_3$ are orthogonal to their corresponding planes $\Pi_2$ and $\Pi_3$, they must also be parallel to $\Pi_1$. We will see in a following section that all parallel rays intersect with the $\Pi_{\infty}$ at the same vanishing point. So the intersection of the rays $d_2$ and $d_3$ with $\Pi_{\infty}$ will lie in the line $l$.

As a result, the line $l$ of intersection between a plane and $\Pi_{\infty}$ is in polar-pole relationship with the point of intersection $d$ between the ray normal to the plane and $\Pi_{\infty}$! And once again, this relationship is preserved under projective transformations.

3.2.4. The dual absolute quadric

Since the absolute conic is defined in the limit $k\rightarrow \infty$, we can not write a explicit matrix parametrizing it. However, we can resort to its dual, termed the dual absolute quadric $Q^*_{\infty}$, which fully defines it:

$$ \begin{equation} Q^*_{\infty}=\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \end{equation} $$

For simplicity, we will just term it $W=Q^*_{\infty}$.

3.2.5. Angles between planes

The angle between two planes $\Pi_1=[a_1, b_1, c_1, d_1]^T$ and $\Pi_2=[a_2, b_2, c_2, d_2]^T$ in the Euclidean space is given by:

$$ \begin{equation} \cos(\theta) = \frac{n_1^T\cdot n_2}{\sqrt{(n_1^T\cdot n_1)(n_2^T\cdot n_2)}} \end{equation} $$

where $n_i=[a_i, b_i, c_i]^T$ is the normal vector of the plane $\Pi_i$. Given the expression for the dual absolute quadric $W$, we can tweak this equation to directly measure the angle in terms of $p_1$ and $p_2$:

$$ \begin{equation} \cos(\theta) = \frac{p_1^T\cdot W\cdot p_2}{\sqrt{(p_1^T\cdot W\cdot p_1)(p_2^T\cdot W\cdot p_2)}} \end{equation} $$

4. Camera calibration

In this section we will focus on how we can retrieve the intrinsic matrix $K$. The absolute conic and its projection onto the image plane play a key role in this process, so it should make sense now why we have spent so much time discussing them.

As a reminder, $K$ can be expressed as:

$$ \begin{equation} K=\begin{bmatrix} f_x & s & \frac{W}{2}\\ 0 & f_y & \frac{H}{2}\\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \end{equation} $$

where $f_x$ and $f_y$ are the focal lengths in the x and y directions, $s$ is the skew factor, and $W$ and $H$ are the width and height of the image in pixels.

4.1 Angle between rays

Say we have two points in the observed 2D image, $x_1$ and $x_2$. They back-project to two rays with direction vectors $d_1$ and $d_2$, passing through the camera center and each of them, respectively.

The angle between the two rays in the Euclidean space is given by:

$$ \begin{equation} \cos(\theta) = \frac{d_1^T\cdot d_2}{\sqrt{(d_1^T\cdot d_1)(d_2^T\cdot d_2)}} \end{equation} $$

We can choose the camera coordinate system so its origin is at the camera center, and the $z$-axis is aligned with the optical axis. This makes computations much easier, since the homography matrix simplifies to

$$ \begin{equation} H= K \cdot \left[\; I\;\; | \;\;\ 0\;\;\right ] \end{equation} $$

Any point in the ray $\tilde{x} = [\lambda d^T, 1]^T$ can be projected to the image plane by:

$$ \begin{equation} x = H \cdot \tilde{x} = K \cdot \left[\; I\;\; | \;\;\ 0\;\;\right ] \cdot \begin{bmatrix} d \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} = K \cdot d \end{equation} $$

where we got rid of $\lambda$ since the projection is defined up to scale. As a result, the angle can be expressed as

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} \cos(\theta) &= \frac{d_1^T\cdot d_2}{\sqrt{(d_1^T\cdot d_1)(d_2^T\cdot d_2)}} \\ &= \frac{x_1^T\cdot (K^{-T}\cdot K^{-1})\cdot x_2}{\sqrt{x_1^T\cdot (K^{-T}\cdot K^{-1})\cdot x_1} \sqrt{x_2^T\cdot (K^{-T}\cdot K^{-1})\cdot x_2}} \end{split} \end{equation} $$

4.2. The image of the absolute conic

In order to find the image of the absolute conic, denoted by $\omega$, we first need to figure out how the plane at infinity $\Pi_{\infty}$ is mapped to the image plane $\Pi$.

Points at infinity take the form $X_{\infty}=[d^T, 0]^T$ and are mapped to:

$$ \begin{equation} x_{\infty} = K \cdot \left[\; R\;\; | \;\;\ T\;\;\right ] \cdot \begin{bmatrix} d \\ 0 \end{bmatrix} = K \cdot R \cdot d \end{equation} $$

which implies the mapping between $\Pi_{\infty}$ and $\Pi$ is given by the homography matrix:

$$ \begin{equation} H = K \cdot R \end{equation} $$

which does not depend on the camera position at all!

Since the absolute conic $\Omega_{\infty}$ lies in $\Pi_{\infty}$, its image $\omega$ must lie in $\Pi$. Points in the absolute conic satisfy:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} x_1^2 + x_2^2 + x_3^2 = 0 \\ x_4 = 0 \end{split} \end{equation} $$

so they satisfy the conic relationship $d^T\cdot I \cdot d = 0$, i.e., $\Omega_{\infty}=I$ for points at infinity. We know how to project a conic under the homography transform, so we get

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} \omega &= H^{-T}\cdot I\cdot H^{-1} \\ &= (K\cdot R)^{-T}\cdot I\cdot (K\cdot R)^{-1} \\ &= K^{-T}\cdot R\cdot R^{-1}\cdot K^{-1} \\ \end{split} \end{equation} $$

So we finally make sense of why we cared about the absolute conic in the first place: it is the image of the absolute conic under the homography transform!

$$ \begin{equation} \omega = K^{-T}\cdot K^{-1} \end{equation} $$

Or equivalently:

$$ \begin{equation} \omega ^{-1} = K\cdot K^T \end{equation} $$

where $\omega^*=\omega^{-1}$ is the dual image of the absolute conic.

Once we find out $\omega$, we can retrieve the intrinsic matrix $K$. To do so, we simply need to decompose $\omega$ into a product of an upper-triangular matrix with positive diagonal entries and its transpose. This is precisely what the Cholesky decomposition guarantees to provide a unique solution for!

There’s still one missing piece though: how do we find $\omega$? Let us see a few important relationships that will help us in this task.

4.2.1. Angles and orthogonality

Combining the equations for the angle between two rays passing through the camera center and the definition of $\omega$, we get:

$$ \begin{equation} \cos(\theta) = \frac{x_1^T\cdot \omega \cdot x_2}{\sqrt{x_1^T\cdot \omega \cdot x_1} \sqrt{x_2^T\cdot \omega \cdot x_2}} \end{equation} $$

Thus, the rays passing through the camera center are orthogonal if their image projections $x_1$ and $x_2$ satisfy:

$$ \begin{equation} x_1^T\cdot \omega \cdot x_2 = 0 \end{equation} $$

which means they are conjugate points with respect to the image of the absolute conic $\omega$.

A line $l$ in the image back projects to a plane $\Pi$ passing through the camera center. The normal ray to the plane, with direction $d$, intersects the image at point $x$, as illustrated below.

We saw earlier that there is a pole-polar relationship w.r.t. the absolute conic $\Omega_\infty$ between:

- The line $l_\infty$ of intersection between a plane $\Pi$ with $\Pi_{\infty}$

- The point of intersection $x_\infty$ between the normal ray $d$ to the plane and $\Pi_{\infty}$

Since the pole-polar relationship is preserved under projective transformations, we can write:

$$ \begin{equation} l_\infty = \omega \cdot x_\infty \end{equation} $$

So to sum up:

- Two points back projecting to orthogonal rays are conjugate points w.r.t. the image of the absolute conic $\omega$.

- A point and a line back projectingto a ray and plane orthogonal to each other are in pole-polar relationship w.r.t. $\omega$.

4.2.2. Planes and circular points

The absolute conic can be interpreted as the intersection between any sphere and the plane at infinity $\Pi_{\infty}$. A sphere is defined by points $x=[x_1, x_2, x_3, x_4]^T$ that satisfy:

$$ \begin{equation} x^T \cdot S \cdot x = x^T \cdot \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & -r^2 \end{bmatrix} \cdot x = 0 \end{equation} $$

There is a set of points that satisfy this equation while lying at the infinity plane $\Pi_{\infty}$:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} x_1^2 + x_2^2 + x_3^2 = 0 \\ x_4 = 0 \end{split} \end{equation} $$

which happens to match the definition of $\Omega_{\infty}$. So we can interpret the absolute conic as the intersection between any sphere and the infinity plane.

Say we take a plane $\Pi$ that instersects with the shpere at a circle parametrized by conic $C$. We know that:

- The intersection between the circle and $\Pi_{\infty}$ must lie in the intersection between the sphere and $\Pi_{\infty}$, i.e., the absolute conic $\Omega_{\infty}$.

- The intersection between the circle and $\Pi_{\infty}$ must lie in the intersection between the plane and $\Pi_{\infty}$, i.e., the line $l_{\infty}$.

- Any circle intersects with the line at infinity $l_\infty$ at the circular points $\mathbf{I}$ and $\mathbf{J}$.

As a result, the circular points $\mathbf{I}=[1, i, 0]^T$ and $\mathbf{J}=[1, -i, 0]^T$ are the intersection between $\Omega_{\infty}$ and $l_{\infty}$. Consequently, the circular points lie in the absolute conic $\omega$!

So say we are able to find the homography matrix $H = [\mathbf{h_1}, \mathbf{h_2}, \mathbf{h_3}]$ that maps a plane in the 3D world to the image. We can treat that plane as a 2D space and project its circular points to the image:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} \mathbf{i} & = H\cdot \mathbf{I} = [\mathbf{h_1}, \mathbf{h_2}, \mathbf{h_3}]\cdot \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ i \\ 0 \end{bmatrix} = \mathbf{h_1} + i\mathbf{h_2} \\ \mathbf{j} & = H\cdot \mathbf{J} = [\mathbf{h_1}, \mathbf{h_2}, \mathbf{h_3}]\cdot \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ -i \\ 0 \end{bmatrix} = \mathbf{h_1} - i\mathbf{h_2} \end{split} \end{equation} $$

Since the circular points lie in the absolute conic, their projection must lie in $\omega$. Thus it will satisfy:

$$ \begin{equation} (\mathbf{h_1} \pm i\mathbf{h_2})\cdot \omega \cdot (\mathbf{h_1} \pm i\mathbf{h_2}) = 0 \end{equation} $$

which implies both the real and imaginary parts of the equation satisfy:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} \mathbf{h_1}^T\cdot \omega \cdot \mathbf{h_1} &= \mathbf{h_2}^T\cdot \omega \cdot \mathbf{h_2} \\ \mathbf{h_1}^T\cdot \omega \cdot \mathbf{h_2} &= 0 \end{split} \end{equation} $$

4.2.3. The vanishing points

As we have seen, the projective transform is able to map the region of infinity to the image plane. Since all parallel lines intersect with the infinity line at the same vanishing point, we can use this property to find the vanishing points in the image. The figure below illustrates how this vanishing point arises from the perspective projection.

Any 3D point in the line driven by direction $d=[d_x,d_y,d_z, 0]$ passing through point $A=[A_x, A_y, A_z, 1]$ can be parametrized as:

$$ \begin{equation} X(\lambda) = A + \lambda d \end{equation} $$

where $\lambda$ is a scalar. The projection of this line in the image plane is given by:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} x(\lambda) & = H \cdot X(\lambda) \\ &= H\cdot (A + \lambda d) \\ &= H A + \lambda K \left[\; R\;\; | \;\;\ T\;\;\right ] \cdot \begin{bmatrix} d \\ 0 \end{bmatrix} \\ &= a + \lambda KRd \end{split} \end{equation} $$

The vanishing point $v$ is given in the limit $\lambda \rightarrow \infty$, so we can write:

$$ \begin{equation} v = \lim_{\lambda \rightarrow \infty} x(\lambda) = a + \lambda KRd = KRd \end{equation} $$

where $\lambda$ disappears since the projection is defined up to scale. Notice how the vanishing point only depends on the direction of the line $d$ and not on the point $A$, proving that all parallel share the same vanishing point.

Another way to think about the vanishing point is as the projection intersection between the line $D$ the plane at infinity $\Pi_{\infty}$. We saw earlier that point of intersection $x_\infty$ between the line $D$ and $\Pi_{\infty}$ is given by $X_\infty = [d^T, 0]^T$. So the vanishing point $v$ is given by its projection in the image plane:

$$ \begin{equation} v = K \left[\; R\;\; | \;\;\ T\;\;\right ] \cdot X_\infty = KRd \end{equation} $$

Therefore the vanishing point for lines parallel to $d$ is simply the intersection $v$ between the image plane with a ray passing through the camera center and the direction $d$.

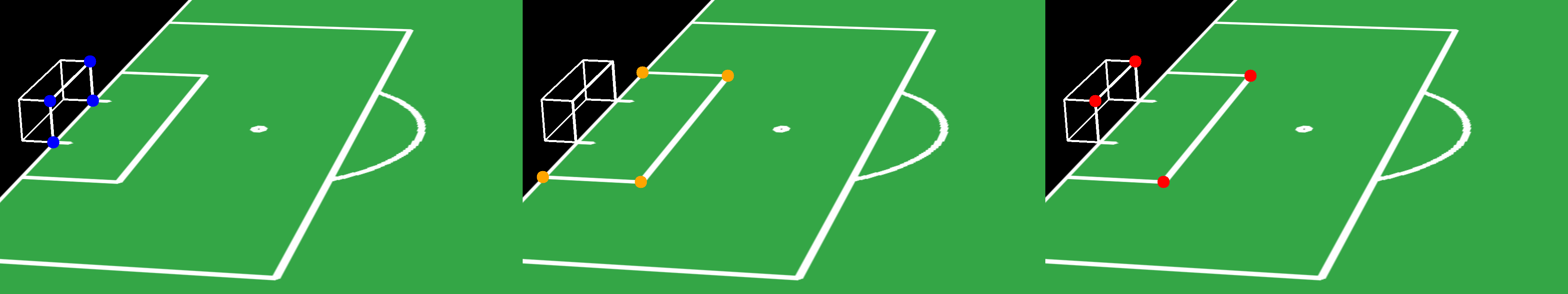

The script below illustrates the concept of the vanishing points. You can tweak the camera parameters to see how the vanishing points change. Notice how the 3D location does not affect them at all, as expected from the previous equation.

(a) 3D World View

(b) Camera View

Since the vanishing point is shared for all parallel rays, we can focus on the rays passing through the camera center. The angle between such rays was determined earlier and it is thus valid for vanishing points:

$$ \begin{equation} \cos(\theta) = \frac{v_1^T\cdot \omega \cdot v_2}{\sqrt{v_1^T\cdot \omega \cdot v_1} \sqrt{v_2^T\cdot \omega \cdot v_2}} \end{equation} $$

This implies that the vanishing points for orthogonal rays satisfy_

$$ \begin{equation} v1^T\cdot \omega \cdot v2 = 0 \end{equation} $$

Given the point/line duality, a similar result can be derived for vanishing lines. They arise from the intersection between a plane $\Pi$ and the plane at infinity $\Pi_{\infty}$. We can compute the angle between two planes from the projection of their vanishing lines according to:

$$ \begin{equation} \cos(\theta) = \frac{l_1^T\cdot \omega^{-1} \cdot l_2}{\sqrt{l_1^T\cdot \omega^* \cdot l_1} \sqrt{l_2^T\cdot \omega^{-1} \cdot l_2}} \end{equation} $$

So to sum up, we have the three following orthogonality relationships:

- The vanishing points of perpendicular rays satisfy: $$ \begin{equation} v_1^T\cdot \omega \cdot v_2 = 0 \end{equation} $$

- The vanishing lines of perpendicular planes satisfy: $$ \begin{equation} l_1^T\cdot \omega^{-1} \cdot l_2 = 0 \end{equation} $$

- If a line is perpendicular to a plane, their respectives vanishing point $v$ and vanishing line $l$ satisfy: $$ \begin{equation} l=\omega \cdot v \end{equation} $$

4.3. Retrieving the intrinsic matrix

Recall our goal here We are trying to find the intrinsic matrix $K$ given the projection of the 3D world captured in the image. We have seen that the image of the absolute conic $\omega$ is a key piece in this puzzle, since it is related to the intrinsic matrix by:

$$ \begin{equation} \omega = K^{-T}\cdot K^{-1} \end{equation} $$

So once we find $\omega$, we can retrieve $K$ by decomposing it into a product of an upper-triangular matrix with positive diagonal entries and its transpose.

We have found a few relationships that can help us find $\omega$, which are summarized in the following table:

| Condition | Constraint |

|---|---|

| Vanishing points $v1$ and $v2$ from perpendicular rays | $v_1^T\cdot \omega \cdot v_2 = 0$ |

| Vanishing lines $l1$ and $l2$ from perpendicular planes | $l_1^T\cdot \omega^{-1} \cdot l_2 = 0$ |

| Vanishing point $v$ and $l$ from perpendicular line and plane | $l=\omega \times v$ |

| Plane imaged with known homography $H = [\mathbf{h_1}, \mathbf{h_2}, \mathbf{h_3}]$ | $\mathbf{h_1}^T\cdot \omega \cdot \mathbf{h_1} = \mathbf{h_2}^T\cdot \omega \cdot \mathbf{h_2}$ $\mathbf{h_1}^T\cdot \omega \cdot \mathbf{h_2} = 0$ |

| No skew | $\omega_{12} = \omega_{21} = 0$ |

| Unit aspect ratio | $\omega_{11} = \omega_{22}$ |

Since $\omega$ is a symmetric matrix, we have 6 unknowns to find. We therefore need at least 6 constraints to solve for it. The process of calibrating the camera would look something like:

- Parametrize $\omega$ as a vector $w=[w_1, w_2, w_3, w_4, w_5, w_6]^T$, where $$ \begin{equation} \omega = \begin{bmatrix} w_1 & w_2 & w_4 \\ w_2 & w_3 & w_5 \\ w_4 & w_5 & w_6 \end{bmatrix} \end{equation} $$

- Find at least 6 constraints from the relationships above and write them in the form $a_i^T\cdot w = 0$.

- Stack the constraints in a matrix $A$ to form a linear system of equations $Aw=0$.

- Solve the system using the SVD decomposition to find the null space of $A$.

- Decompose $\omega$ into $K$ using the Cholesky decomposition.

5. Examples

In this section we will see a few examples of how the concepts we have discussed can be applied in practice.

5.1. Calibration from two vanishing points

Say we have some prior knowledge about our camera, i.e., we know its principal point is at the center of the image, the pixels are squared and there is no skew. We can write the intrinsic matrix $K$ as:

$$ \begin{equation} K=\begin{bmatrix} f & 0 & \frac{W}{2}\\ 0 & f & \frac{H}{2}\\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \end{equation} $$

where $f$ is the focal length, $W$ and $H$ are the width and height of the image in pixels.

We have seen two orthogonal rays have vanishing points that satisfy:

$$ \begin{equation} v_1^T\cdot \omega \cdot v_2 = 0 \end{equation} $$

or alternatively

$$ \begin{equation} v_1^T\cdot K^{-T}\cdot K^{-1} \cdot v_2 = 0 \end{equation} $$

Replacing $K$ in the equation above, we get:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{bmatrix} v_{1x} & v_{1y} & 1 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{f} & 0 & 0\\ 0 & \frac{1}{f} & 0\\ -\frac{W}{2f} & -\frac{H}{2f} & 1 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \frac{1}{f} & 0 & -\frac{W}{2f}\\ 0 & \frac{1}{f} & -\frac{H}{2f}\\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} v_{2x} \\ v_{2y} \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} = 0 \end{equation} $$

and we can now expand to:

$$ \begin{equation} \frac{1}{f^2} \begin{bmatrix}v_{1x} - \frac{W}{2} & v_{1y} - \frac{H}{2} & f \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix}v_{2x} - \frac{W}{2} \\ v_{2y} - \frac{H}{2} \\ f \end{bmatrix} = 0 \end{equation} $$

This equation leads to:

$$ \begin{equation} f = \sqrt{-\left(v_{1x} - \frac{W}{2}\right)\left(v_{2x} - \frac{W}{2}\right) - \left(v_{1y} - \frac{H}{2}\right)\left(v_{2y} - \frac{H}{2}\right)} \end{equation} $$

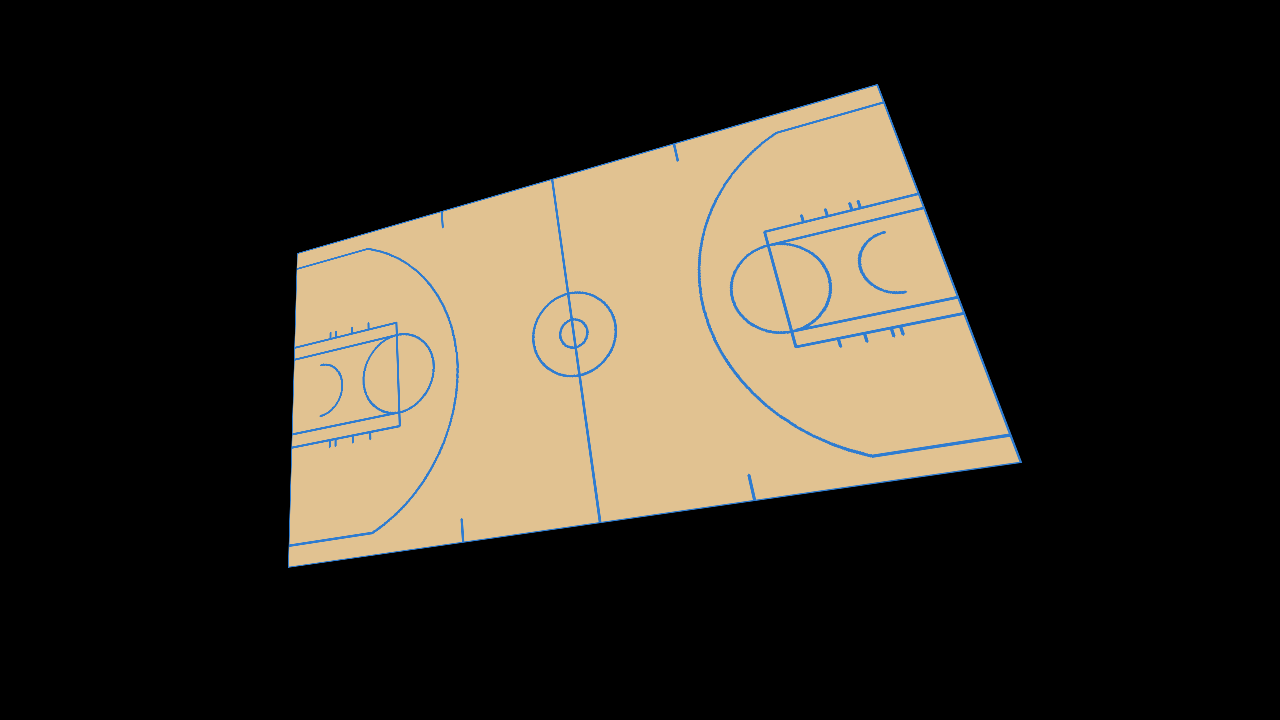

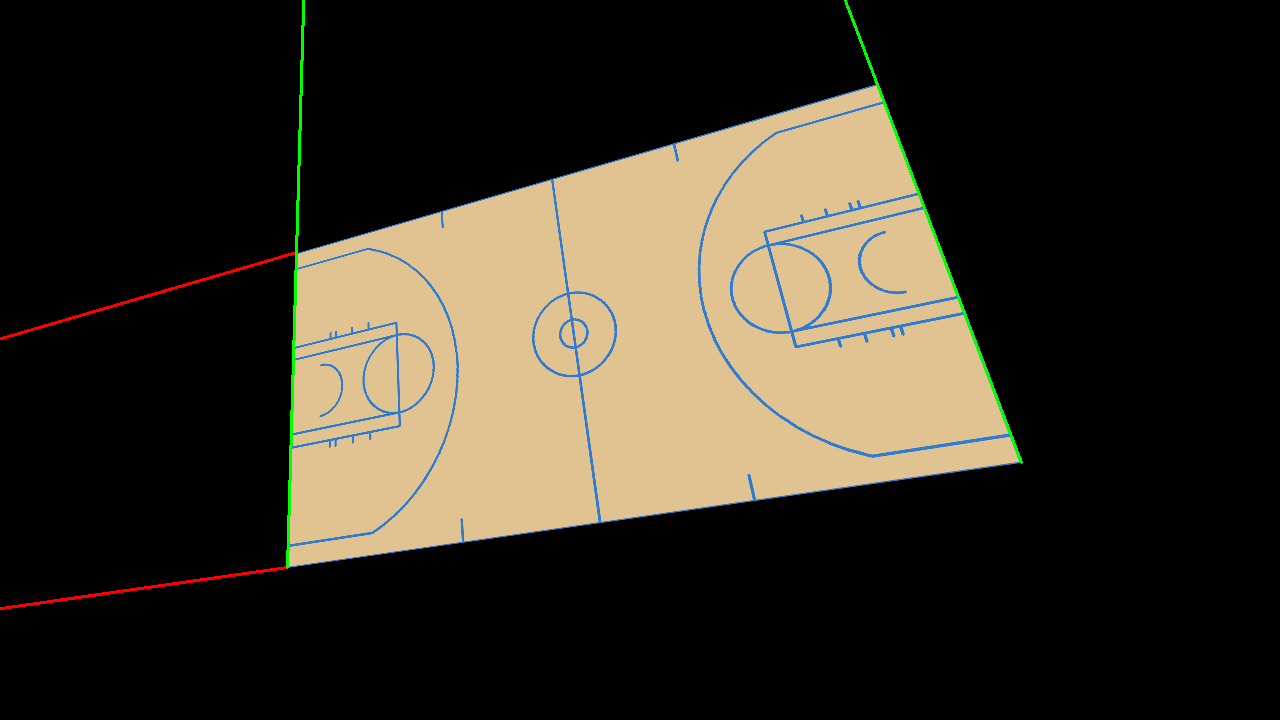

So imagine we get the following $1280\times 640$ image, which we synthetically generated with $f=350$:

We know the court has rectangular shape in the 3D world, so the end lines (the lines behind the baskets) and the sidelines (the lines next to the benches) are perpendicular to each other. Therefore, their corresponding vanishing points in the image must satisfy the equation above.

We simply need to locate the end/sidelines on the image, parametrize them and extend them to find their intersection.

Following this procedure for the basketball court above, we get the following vanishing points, which happen to lie outside the image:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} v_1 &= \begin{bmatrix} -1815.16 & 868.08 \end{bmatrix} \\ v_2 &= \begin{bmatrix} 341.78 & -1322.13 \end{bmatrix} \end{split} \end{equation} $$

Finally, we just need to replace these values in the equation above to find the focal length:

$$ \begin{equation} \boxed{f = 350} \end{equation} $$

which indeed matches the ground-truth focal length of the camera used to capture the image.

Note: you can give it a try by simply running this script. In order to do so, just install the repository (poetry install) and then run

poetry run python -m projective_geometry focal-length-from-orthogonal-vanishing-points-demo

5.2. Calibration from three linearly independent planes

Now we are going to try to calibrate the camera from the homographies that maps three linearly independent (known) planes in the 3D world and their corresponding projections in the image. To make the estimation more robust, we will assume no skew and squared pixels as well, so the intrinsic matrix $K$ can be written as:

$$ \begin{equation} K=\begin{bmatrix} f & 0 & x\\ 0 & f & y\\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \end{equation} $$

where $f$ is the focal length, $W$ and $H$ are the width and height of the image in pixels. This allows to write

$$ \begin{equation} \omega = K^{-T}\cdot K^{-1} = \frac{1}{f^2} \cdot \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & -x \\ 0 & 1 & -y \\ -x & -y & x^2 + y^2 + f^2 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \omega_{1} & 0 & \omega_{2} \\ 0 & \omega_{1} & \omega_{3} \\ \omega_{2} & \omega_{3} & \omega_{4} \end{bmatrix} \end{equation} $$

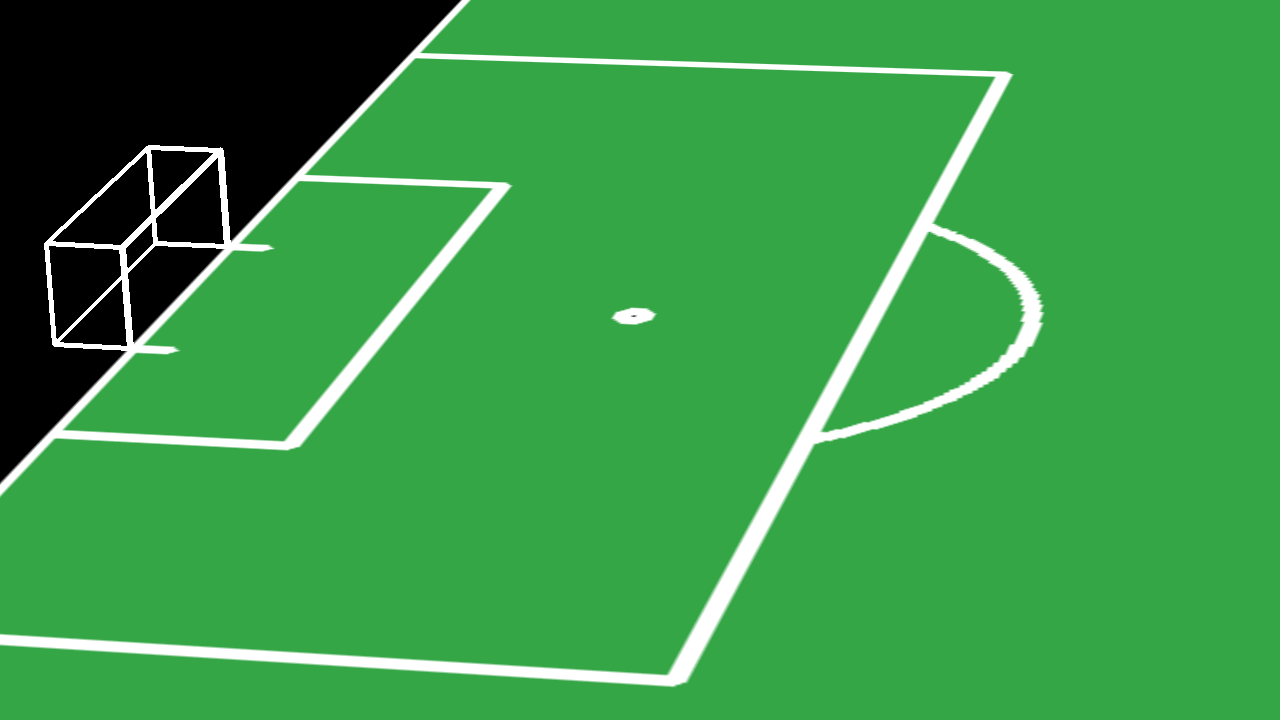

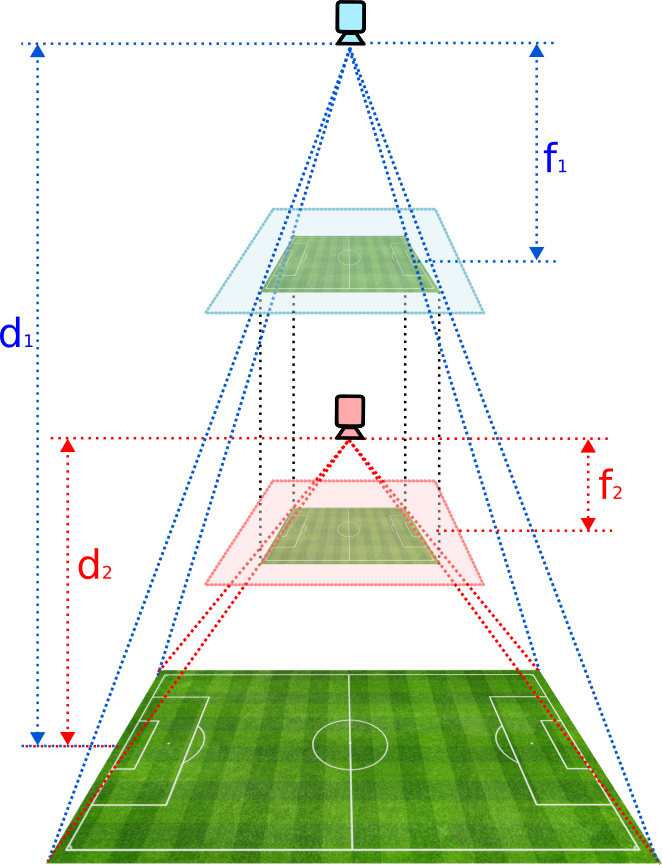

The image below shows a synthetic soccer pitch captured using a pinhole camera with no skew, squared pixels, principal point at $(x, y)=(640, 360)$ and focal length $f=4763$.

We now identify three linearly independent planes and proceed as follows in order to find the homography that maps them to the image:

- Locate four non-collinear points $\{ p_i \} _{i=1}^{4}$ from each plane in the image

- Find an orthonormal basis for the plane in the 3D world. Gram-Schmidt process, which we have discussed in an earlier post, can be used to find such basis.

- Express each of the corresponding real world points $\{ P_i \} _{i=1}^{4}$ in the basis

- Find the homography matrix $H_i=[\mathbf{h_{i1}}, \mathbf{h_{i2}}, \mathbf{h_{i3}}]$ that maps $$\{ P_i \} _{i=1}^{4} \rightarrow \{ p_i \} _{i=1}^{4}$$

- Get two constraints based on the circular points, as seen earlier: $$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} \mathbf{h_{i1}}^T\cdot \omega \cdot \mathbf{h_{i1}} &= \mathbf{h_{i2}}^T\cdot \omega \cdot \mathbf{h_{i2}} \\ \mathbf{h_{i1}}^T\cdot \omega \cdot \mathbf{h_{i2}} &= 0 \end{split} \end{equation} $$

- Rewrite each constraint in the form $a_i^T\cdot w = 0$, where $w=[\omega_1, \omega_2, \omega_3, \omega_4]^T$

- Stack the constraints in a matrix $A$ to form a linear system of equations $Aw=0$

- Solve the system using the SVD decomposition to find the null space of $A$

- Retrieve focal length $f$ and principal point $(x, y)$ from $\omega$ by: $$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} f &= \sqrt{\omega_1} \\ x &= -\frac{\omega_2}{\omega_1} \\ y &= -\frac{\omega_3}{\omega_1} \end{split} \end{equation} $$

Using the three planes shown above and following the steps described, we find the following intrinsic matrix:

$$ \begin{equation} \boxed{K=\begin{bmatrix} 4820 & 0 & 640\\ 0 & 4820 & 360\\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}} \end{equation} $$

which resembles reasonably well the ground-truth intrinsic matrix used to generate the image.

Note: you can give it a try by simply running this script. In order to do so, just install the repository (poetry install) and then run

poetry run python -m projective_geometry intrinsic-from-three-planes-demo

6. Conclusion

In this article we have seen how the image of the absolute conic $\omega$ can be used to calibrate a camera through the different relationships it gives rise to:

- Vanishing points corresponding to orthogonal rays.

- Vanishing lines corresponding to orthogonal planes

- Vanishing points and lines corresponding to orthogonal rays and planes

- Circular points

Furthermore, we have seen a couple practical examples of how to calibrate a camera using these relationships. However, the calibration process can be quite sensitive to noise, so it is important to have a good set of constraints to ensure the accuracy of the calibration.

7. Appendix

In an earlier post, we mentioned that the KRT parametrisation is not retrievable in general if we only have access to the projection of a 2D plane from the 3D world. We illustrated the unresolvable ambiguity with the following figure:

But we have just shown throughout this article that the intrinsic matrix $K$ can be retrieved from the image of the absolute conic $\omega$. So how can we reconcile these two statements?

Well, the KRT parametrisation is retrievable except for one case: when the image plane is parallel to the 2D plane we are projecting from the 3D world. And that is precisely what the previously figure shows. It depicts how a soccer pitch is captured from a zenithal view, i.e., the image plane is parallel to the ground plane (XY plane). So why does that give rise to an ambiguity?

Notice that all the constraints we have for the image of the absolute conic $\omega$ rely on being able to locate the image projection for geometric features that live in the real of infinity: the vanishing points, the vanishing lines, the circular points. That projection is given by the homography matrix that maps the 2D plane in question, to the image plane.

For the ambiguous case, those two planes are parallel. Without loss of generality, we can assume the 2D planes are parallel to the XY plane, and the origin of coordinates is at the camera center, as illustrated below:

The homography matrix between the 2D planes is thus given by

$$ \begin{equation} H = \begin{bmatrix} f & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & f & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & d \end{bmatrix} \end{equation} $$

where $f$ is the focal length and $d$ is the distance between the two planes. Since the homography is defined up to scale, you can already see that scaling $f$ and $d$ by the same factor will not change the image of the 2D plane in the image plane. This is the ambiguity we are talking about.

But what if we were to find $\omega$? Well, let us see. A point in the 3D ground can be expressed relative to that 2D plane in the form $P=[X, Y, 0]$. Therefore its projection $p$ onto the image plane is given by:

$$ \begin{equation} p = H\cdot P = \begin{bmatrix} f & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & f & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & d \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} X \\ Y \\ 0 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} f\cdot X \\ f\cdot Y \\ 0 \end{bmatrix} \end{equation} $$

so it projects to infinity as well! Therefore we will not be able to locate the vanishing points, vanishing lines, or circular points in the image, and we will not be able to retrieve the image of the absolute conic $\omega$.

8. References

- Richard Hartley and Andrew Zisserman (2000), Multiple View Geometry in Computer Vision, Cambridge University Press.

- Henri P. Gavin (2017), CEE 629 Lecture Notes. System Identification Duke University, Total Least Squares

- OpenCV Libary: Basic concepts of the homography explained with code

- Conic Dual to Circular Points

- Cholesky decomposition: Wikipedia

- Absolute Conic-based Single View to 3D