Table of Contents

1. Introduction: Perspective-n-Point (PnP) problem

We have seen in an earlier article how we can estimate the homography matrix $H$ that characterizes the projective transform between two images. This matrix takes the form:

$$ \begin{equation} H= K \cdot \left[\; R^T\;\; | \;\;-R^T\cdot\vec{t}\;\;\right ] \end{equation} $$

In another previous post, we then studied how to calibrate the camera by retrieving the intrinsic matrix $K$, parametrised by the focal length, the skew coefficient, and the principal point.

In this article we will focus on the camera pose retrieval problem, which consists of retrieving the camera orientation $R$ and the translation vector $\vec{t}$ that characterize the extrinsic matrix $E=\left[\; R^T\;\; | \;\;-R^T\cdot\vec{t}\;\;\right ]$.

Our goal then is to do so from a set of $n$ 3D points and their corresponding 2D projections in the image. This problem is known as the Perspective-n-Point (PnP) problem, and it is a fundamental problem in computer vision.

2. Degrees of freedom

The first question that comes to mind is: how many points do we need to retrieve the camera pose? To gain some intuition, we can think of a 3D cube in the world coordinate system. Varying the camera pose, i.e., its location and orientation, is equivalent to keeping still the camera and applying a rigid transformation to the cube.

Without any constraints (P0P problem), the rigid transformation has 6 degrees of freedom (DOF), 3 for the rotation and 3 for the translation. This is illustrated below, where you can tweak the different parameters.

(a) 3D World View

(b) Camera View

Now say we are able to map one point in the 3D world to its corresponding 2D projection in the image. This is known as the P1P problem. In our case, this would be the corner highlighted in green in the 3D cube. With the constraint that the green point cannot move in the image, how many degrees of freedom do we have left? Well, we can rotate the cube around any axis, that is 3 DOFs. We can also move the cube along the orange ray from that green corner to the pinhole, which is another DOF. But we can not shift the cube in the plane perpendicular to the ray, so we have removed 2 DOFs. This leaves us with 4 DOFs for the P1P problem, as illustrated below.

(a) 3D World View

(b) Camera View

Let us add a second point, displayed in green. This is the P2P problem. We still can not shift the cube along the plane perpendicular to the rays any of the marked corners to the pinhole, so those 2 DOFs remain gone. Furthermore, we can only rotate the cube around the axis given by the line connecting the two green points. Any other rotation would move the green points in the image, so that is another 2 DOFs gone.

How about shifting, do you see any way to do that? This one is a bit tricky, but if you think about it, you will see the only way to shift the cube without the green corners moving in the image is by doing so along the orange rails defined by the rays from the green corners to the pinhole. Since those rays are not parallel (they intersect in the pinhole), we need to rotate slightly the cube as we shift it so both corners stay in their corresponding rail. Play around with the sliders below to convince yourself!

(a) 3D World View

(b) Camera View

You can see the pattern now, each additional point seems to remove 2 DOFs. With a third non-collinear point we get the P3P problem, which removes almost entirely the freedom to move the cube. There is a slight caveat we will discuss later on, but this is the problem we will focus on in this article.

3. Mapping 3D points to camera coordinates

The P3P problem can be stated as follows. We have 3 non-collinear points in the 3D world, $p_1$, $p_2$, and $p_3$, and their corresponding 2D projections in the image, $P_1$, $P_2$, and $P_3$. The image is captured with a calibrated camera, i.e., with known focal length $f$. The goal is to retrieve the camera pose, i.e., the rotation matrix $R$ and the translation vector $\vec{t}$.

The set up is illustrated below. Notice we define three different coordinate systems:

- The world coordinate system, with origin $O$ and axes $\hat{x}$, $\hat{y}$, and $\hat{z}$.

- The camera coordinate system, with origin at the camera center $T$ and axes $\hat{x’}$, $\hat{y’}$, and $\hat{z’}$ aligned so that $\hat{z’}$ is the optical axis.

- The image coordinate system, with origin at the top left corner of the image and axes $\hat{X}$ and $\hat{Y}$.

For the time being, we will operate in the camera coordinate system. Our first stepp will be to compute the angles between the rays from the camera center to the 3D points, $[\alpha, \beta, \gamma]$, as shown below:

The image points can be expressed in the world coordinate system. The image below illustrates the setup, where the image plane is aligned with the $\hat{X’}\hat{Y’}$ plane, and the optical axis is aligned with the $\hat{Z’}$ axis. Without loss of generality, we will assume the principal point is at the center of the image.

We can therefore express express the image points in the camera coordinate system as:

$$ \begin{equation} p_i = \begin{bmatrix} u_i - \frac{W}{2} \ v_i - \frac{H}{2} \ f \end{bmatrix} \end{equation} $$

The angles between the rays are then given by

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} \alpha &= \arctan\left(\frac{p_1 \cdot p_2}{|p_1| \cdot |p_2|}\right) \\ \beta &= \arctan\left(\frac{p_2 \cdot p_3}{|p_2| \cdot |p_3|}\right) \\ \gamma &= \arctan\left(\frac{p_3 \cdot p_1}{|p_3| \cdot |p_1|}\right) \end{split} \end{equation} $$

Let us now move to the 3D world points $P_i$. The rays pass through them, so we can leverage the angles we just computed to retrieve the distances $s_i$ between the camera center $O$ and these world points $P_i$.

We start by computing the distance between world points themselves, which is known:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} a &= |P_2 - P_3| \\ b &= |P_3 - P_1| \\ c &= |P_1 - P_2| \end{split} \end{equation} $$

There are multiple methods to determine the distances $s_i$. Grunert’s solution relies on the law of cosines, whose proof is provided below for the interested reader, but feel free to skip it.

Law of Cosines

The Law of cosines states that for a triangle with sides $a$, $b$, and $c$, and angles $\alpha$, $\beta$, and $\gamma$ opposite to those sides, the following relation holds: $$ \begin{equation} c^2 = a^2 + b^2 - 2ab\cos(\gamma) \end{equation} $$ We can resort to the Pythagorean theorem to prove this. For a right triangle, the result is straightforward since $\gamma = 90^\circ$ and $\cos(90^\circ) = 0$. We can distinguish two additional cases:Acute triangle ($\gamma < 90^\circ$): $$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} c^2 &= (b\sin(\pi - \gamma))^2 + (a + b\cos(\pi - \gamma))^2 \\\\ &= (b\sin(\gamma))^2 + (a - b\cos(\gamma))^2 \\\\ &= b^2\sin^2(\gamma) + a^2 + b^2\cos^2(\gamma) - 2ab\cos(\gamma) \\\\ &= a^2 + b^2 - 2ab\cos(\gamma) \end{split} \end{equation} $$

Obtuse triangle ($\gamma > 90^\circ$): $$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} c^2 &= (b\sin(\gamma))^2 + (a - b\cos(\gamma))^2 \\\\ &= b^2\sin^2(\gamma) + a^2 + b^2\cos^2(\gamma) - 2ab\cos(\gamma) \\\\ &= a^2 + b^2 - 2ab\cos(\gamma) \end{split} \end{equation} $$

For instance, take the triangle $\overset{\triangle}{OP_1P_3}$. Applying the Law of Cosines, we get:

$$ \begin{equation} s_1^2 + s_3^2 - 2s_1s_3\cos(\beta) = b^2 \end{equation} $$

If we repeat this process for the other two triangles, we get the following equations:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} a^2 &= s_2^2 + s_3^2 - 2s_2s_3\cos(\alpha) \\ b^2 &= s_1^2 + s_3^2 - 2s_1s_3\cos(\beta) \\ c^2 &= s_1^2 + s_2^2 - 2s_1s_2\cos(\gamma) \end{split} \end{equation} $$

We can define the auxiliary variable:

$$ \begin{equation} u = \frac{s_2}{s_1}, \quad v = \frac{s_3}{s_1} \end{equation} $$

Substituting those and rearranging the equations, we get three equations for $s_1$ in terms of $u$ and $v$:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} s_1^2 &= \frac{a^2}{u^2 + v^2 - 2uv\cos(\alpha)} \\ s_1^2 &= \frac{b^2}{1 + v^2 - 2v\cos(\beta)} \\ s_1^2 &= \frac{c^2}{1 + u^2 - 2u\cos(\gamma)} \end{split} \end{equation} $$

If we combine the first two equations and the last two equations, respectively, we get:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} u^2 + \frac{b^2-a^2}{a^2}v^2 - 2uv\cos(\alpha) + \frac{2a^2}{b^2}v\cos(\beta) - \frac{a^2}{b^2} &= 0 \\ u^2 - \frac{c^2}{b^2}v^2 + 2v\frac{c^2}{b^2}\cos(\beta) - 2u\cos(\gamma) + \frac{b^2-c^2}{b^2} &= 0 \end{split} \end{equation} $$

From the first equation we have:

$$ \begin{equation} u^2 = \frac{a^2-b^2}{a^2}v^2 + 2uv\cos(\alpha) - \frac{2a^2}{b^2}v\cos(\beta) + \frac{a^2}{b^2} \end{equation} $$

which we can now replace in the second equation to express $u$ in terms of $v$:

$$ \begin{equation} u = \frac{\left( \frac{a^2-c^2-b^2}{b^2}\right)v^2-2\left(\frac{a^2-c^2}{b^2}\right) v\cos(\beta) + \frac{a^2+b^2-c^2}{b^2}}{2\left(\cos(\gamma) - v\cos(\alpha)\right)} \end{equation} $$

If we plug this back into the first equation, we get a fourth-degree polynomial in $v$:

$$ \begin{equation} A_4v^4 + A_3v^3 + A_2v^2 + A_1v + A_0 = 0 \end{equation} $$

where the coefficients $A_i$ are given by:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} A_4 &= \left( \frac{a^2-c^2-b^2}{b^2}\right)^2 - \frac{4c^2}{b^2}\cos^2(\alpha) \\ A_3 &= 4\left[ \frac{(a^2-c^2)(b^2+c^2-a^2)}{b^4} \cos(\beta) \right. \\ &\left. +\frac{a^2+c^2-b^2}{b^2}\cos(\alpha)\cos(\gamma) + 2\frac{c^2}{b^2}\cos(\alpha)\cos(\beta) \right] \\ A_2 &= 2\left[ \left( \frac{a^2-c^2}{b^2} \right)^2 - 1 +2\left( \frac{a^2-c^2}{b^2} \right)\cos^2(\beta) \right. \\ &\left. + 2\left( \frac{b^2-c^2}{b^2} \right)\cos^2(\alpha) - 4 \left( \frac{a^2+c^2}{b^2} \right)\cos(\alpha)\cos(\beta)\cos(\gamma) \right] \\ &+ 2\left( \frac{b^2-a^2}{b^2} \cos^2(\gamma) \right) \\ A_1 &= 4\left[ \frac{(c^2-a^2)(b^2+a^2-c^2)}{b^4} \cos(\beta) \right. \\ &\left. +\frac{2a^2}{b^2}\cos^2(\gamma)\cos(\beta) + \frac{a^2+c^2-b^2}{b^2}\cos(\alpha)\cos(\gamma) \right] \\ A_0 &= \left( \frac{a^2-c^2+b^2}{b^2} \right)^2 - \frac{4a^2}{b^2}\cos^2(\gamma) \end{split} \end{equation} $$

Once we solve this polynomial equation for $v$, we can compute $u$ using the equation derived above. Then we can obtain the distances $s_i$ by:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} s_1 &= \frac{b^2}{1 + v^2 - 2v\cos(\beta)} \\ s_2 &= us_1 \\ s_3 &= vs_1 \end{split} \end{equation} $$

Notice though the solution is not unique. We can have up to 4 solutions, which is the slight caveat we mentioned earlier. How does this happen? The following animation illustrates it:

So which one is it then? Well, 3 points are not enough to resolve the ambiguity. If we have an extra point though, we could solve the previous problem for different combinations of 3 points and pick the one that satisfies all of them!

Last, we can express the world points in the camera coordinate system as:

$$ \begin{equation} P_i’ = s_i\cdot\frac{p_i}{|p_i|} \end{equation} $$

4. Retrieving the camera pose

So now we have the coordinates of the world points expressed in two different coordinates systems:

- World coordinate system: $P_i = [X_i, Y_i, Z_i]$

- Camera coordinate system: $P_i’ = [X_i’, Y_i’, Z_i’]$

Our goal is to find the camera pose, i.e., the rotation matrix $R$ and the translation vector $T$.

4.1. Noiseless scenario

Without noise corruption, 3 points allow for camera pose retrieval. Recall how the extrinsic matrix allow to transform points from the world to the camera coordinate system:

$$ \begin{equation} P’ = E\cdot P \end{equation} $$

where $E$ is determined from the camera pose as:

$$ \begin{equation} E= \left[\; R^T\;\; | \;\;-R^T\cdot\vec{t}\;\;\right ] \end{equation} $$

With known correspondences between 3 points, we can also find the rigid transform that aligns the world points to the camera points. The process is as follows:

- Compute the vectors: $$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} v_1 = P_1 - P_2, &\quad v_2 = P_1 - P_3 \\ v_1’ = P_1’ - P_2’, &\quad v_2’ = P_1’ - P_3' \end{split} \end{equation} $$

- Shift both to the origin: $$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} v_i &\leftarrow v_i - P_1 \\ v_i’ &\leftarrow v_i’ - P_1' \end{split} \end{equation} $$

- Rotate to map $v_i$ to $v_i’$ using $\Omega=R_{v1}(\phi)\cdot R_n(\theta)$:

- Rotate $v_i$ around $n=v1\times v1’$ by $\theta=\angle(v_1, v_1’) \rightarrow R_n(\theta)$.

- Rotate $v2$ around $v1$ by $\phi=\angle(v_2, v_2’) \rightarrow R_{v1}(\phi)$.

- Shift back to $P_1’$.

The following equations summarizes the process that maps the world points to the camera coordinate system:

$$ \begin{equation} P’ = \begin{bmatrix} I & P_1’ \\ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \cdot \begin{bmatrix} \Omega & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \cdot \begin{bmatrix} I & -P_1 \\ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \cdot P \end{equation} $$

Comparing with the definition of the extrinsic matric, we get

$$ \begin{equation} \left[\; R^T\;\; | \;\;-R^T\cdot\vec{t}\;\;\right ] = \left[\; \Omega\;\; | \;\;-\Omega\cdot P_1 + P_1’\;\;\right ] \end{equation} $$

so the camera pose is given by:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} R &= \Omega^T \\ \vec{t} &= P_1 - \Omega^T\cdot P_1' \end{split} \end{equation} $$

The following animation illustrates the process:

4.2. Noisy scenario

We never have noiseless data in practice, so we need to account for that. Let us see how we can estimate the camera pose in the presence of noise from an arbitrary number of points via Arun’s method.

We can express the camera points as:

$$ \begin{equation} P_i’ = R’\cdot P_i + T + \epsilon_i \end{equation} $$

where $R’=R^T$ and $T=-R^T\cdot\vec{t}$ and $\epsilon_i \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2I)$ is the noise. We can now look for the unknowns $R’$ and $T$ that minimize the error:

$$ \begin{equation} \hat{R’}, \hat{T} = \arg\min_{R’, T} \sum_{i=1}^N \Vert P_i’ - \left(R’\cdot P_i + T\right)\Vert^2 \end{equation} $$

We can simplify this problem by decoupling the rotation and translation estimation. The cost function is minimized when its gradient is zero. We can compute the gradient with respect to $T$ and set it to zero:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} \frac{\partial}{\partial T} \sum_{i=1}^N \Vert P_i’ - \left(R’\cdot P_i + T\right)\Vert^2 &= 0 \\ \sum_{i=1}^N 2\left(R’\cdot P_i - P_i’ + T\right) &= 0 \\ \sum_{i=1}^N \left(R’\cdot P_i - P_i’\right) + N\cdot T &= 0 \end{split} \end{equation} $$

which implies T is the difference between the centroids of the world and camera points, which we denote as $\bar{P}$ and $\bar{P’}$, respectively:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} T &= \left(\frac{1}{N}\sum_{i=1}^N P_i’\right) - R’\cdot\left(\frac{1}{N}\sum_{i=1}^N P_i\right) \\ &= \bar{P’} - R’\cdot\bar{P} \end{split} \end{equation} $$

Our cost function then simplifies to

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} \Sigma^2 &= \sum_{i=1}^N \Vert P_i’ - \left(R’\cdot P_i + \bar{P’} - R’\cdot\bar{P}\right)\Vert^2 \\ &= \sum_{i=1}^N \Vert Q_i’ - R’\cdot Q_i\Vert^2 \end{split} \end{equation} $$

where $Q_i = P_i - \bar{P}$ and $Q_i’ = P_i’ - \bar{P’}$.

We can now estimate the rotation matrix $R’$ by minimizing the cost function:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} \hat{R’} &= \arg\min_{R’} \Sigma^2 \\ &= \arg\min_{R’} \sum_{i=1}^N \Vert Q_i’ - R’\cdot Q_i\Vert^2 \end{split} \end{equation} $$

Let us expand the cost function

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} \Sigma^2 &= \sum_{i=1}^N \Vert Q_i’ - R’\cdot Q_i\Vert^2 \\ &= \sum_{i=1}^N \left(Q_i’^TQ_i’ - 2Q_i’^TR’Q_i + Q_i^TR’^TQ_i\right) \\ &= \sum_{i=1}^N \left(\Vert Q_i’\Vert^2 - 2Q_i’^TR’Q_i + \Vert Q_i\Vert^2\right) \end{split} \end{equation} $$

where we have used the fact that $R’^TR’ = I$. Notice only one term depends on $R’$, so we can define

$$ \begin{equation} F = \sum_{i=1}^N Q_i’^TR’Q_i \end{equation} $$

This way, minimizing $\Sigma^2$ is equivalent to maximizing $F$:

$$ \begin{equation} \hat{R’} = \arg\min_{R’} \Sigma^2 = \arg\max_{R’} F \end{equation} $$

F is a scalar, so its trace is equal to itself:

$$ \begin{equation} F = \text{tr}\left(F\right) = \text{tr}\left(\sum_{i=1}^N Q_i’^TR’Q_i\right) \end{equation} $$

We can use two properties of the trace:

- Linearity property: $\text{tr}(A+B) = \text{tr}(A) + \text{tr}(B)$

- Cyclic property: $\text{tr}(ABC) = \text{tr}(CAB) = \text{tr}(BCA)$

That gets us:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} F &= \text{tr}\left(\sum_{i=1}^N Q_i’^TR’Q_i\right) \\ &= \sum_{i=1}^N \text{tr}\left(Q_i’^TR’Q_i\right) \\ &= \sum_{i=1}^N \text{tr}\left(R’Q_iQ_i’^T\right) \\ &= \text{tr}\left(R’\sum_{i=1}^N Q_iQ_i’^T\right) \\ &= \text{tr}\left(R’\cdot H\right) \end{split} \end{equation} $$

where $H = \sum_{i=1}^N Q_iQ_i’^T$.

Lemma: For any positive definite matrix $A\cdotA^T$ and any orthonormal matrix $B$ $$ \begin{equation} \text{tr}(A\cdot A^T) \geq \text{tr}(B\cdot A\cdot A^T) \end{equation} $$

Proof

Let $A=[a_1, \cdots, a_n]$ and $B$ an orthonormal matrix. Using the definition of the trace and its cyclic property we get: $$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} \text{tr}(B AA^T) &= \text{tr}(A^TB A) \\\\ &= \sum_{i=1}^n a_i^T\cdot \left(B\cdot a_i\right) \end{split} \end{equation} $$ The Cauchy-Schwarz inequality states that for any vectors $x$ and $y$: $$ \begin{equation} x^T\cdot y \leq \sqrt{\Vert x\Vert^2\cdot\Vert y\Vert^2} \end{equation} $$ so we have: $$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} \text{tr}(B AA^T) &= \sum_{i=1}^na_i^T\cdot \left(B\cdot a_i\right) \\\\ &\leq \sum_{i=1}^n\sqrt{\Vert a_i\Vert^2\cdot\Vert B\cdot a_i\Vert^2} \\\\ &= \sum_{i=1}^n\sqrt{\Vert a_i\Vert^2\cdot\Vert a_i\Vert^2} \\\\ &= \sum_{i=1}^n\Vert a_i\Vert^2 \\\\ &= \text{tr}(AA^T) \end{split} \end{equation} $$ which proves the lemma.We can leverage this lemma by means of the almighty SVD decomposition of H:

$$ \begin{equation} H = U\cdot D\cdot V^T \end{equation} $$

where $U$ and $V$ are orthogonal matrices and $D=\text{diag}(d_1, \cdots, d_N)$ is a diagonal matrix with the singular values $d_i$ of $H$. Since the singular values are real non-negative numbers, they take the form $d_i=\lambda_i^2$, so we can express $D$ as

$$ \begin{equation} D = \Lambda^2 \end{equation} $$

where $\Lambda = \text{diag}(\lambda_1, \cdots, \lambda_N)$. H becomes:

$$ \begin{equation} H = U\cdot \Lambda^2\cdot V^T \end{equation} $$

If we define the orthonormal matrix $X = V\cdot U^T$ and we compute the product

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} X\cdot H &= V\cdot U^T\cdot U\cdot \Lambda^2\cdot V^T \\ &= \left( V\cdot \Lambda \right)\cdot \left( V\cdot \Lambda \right)^T \end{split} \end{equation} $$

which is a symmetric and positive definite matrix. We can now apply the lemma, with $A=V\cdot \Lambda$, which implies

$$ \begin{equation} \text{tr}(X\cdot H) \geq \text{tr}(B\cdot X\cdot H) \end{equation} $$

for any orthonormal matrix $B$. Furthermore, notice that $C=B\cdot X$ is also an orthonormal matrix, so we have:

$$ \begin{equation} \text{tr}(X\cdot H) \geq \text{tr}(C\cdot H) \end{equation} $$

That is to say, amongs all orthonormal matrices $M$, $X$ maximizes the trace of the product $M\cdot H$.

This is closely related to our problem at hand. Our goal was to find a rotation matrix $R’$ that maximizes the trace of $R’\cdot H$.

$$ \begin{equation} \hat{R’} = \arg\max_{R’} F = \arg\max_{R’} \text{tr}\left(R’\cdot H\right) = X \end{equation} $$

Orthonormal matrices correspond to matrices with unitary and orthogonal columns. However, rotation matrices are just a subset of orthonormal matrices, corresponding to those with a determinant of $+1$.

Therefore, if our $X$ has a determinant of +1, we have found the rotation matrix $R’=X$!.

4.3. Handling the reflection case

To understand what is going on, let us focus in the noiseless case. There are three scenarios:

- Points are collinear: there are infinite rotations that minimize the cost function. Any rotation around the line defined by the points will do.

- Points are non-coplanar: there is a unique rotation that minimizes the cost function.

- Points are coplanar but not collinear: there are two unitary matrices that minimize the cost function, a rotation and a reflection.

The last case is the one that causes the ambiguity, since any reflection across the plane all points lie on will also minimize the cost function. The reflection corresponds to $X$ with determinant $-1$.

Notice though that based on the SVD, we can express H as:

$$ \begin{equation} H = \sum_{i=1}^N d_i\cdot u_i\cdot v_i^T \end{equation} $$

where $u_i$ and $v_i$ are the columns of $U$ and $V$, respectively. Since we are dealing with coplanar points, H has rank 2. That implies the singular values satisfy $d_1 > d_2 > d_3=0$, so there is another valid decomposition:

$$ \begin{equation} H = U\cdot D\cdot V’^T \end{equation} $$

where $V’=[v_1, v_2, -v_3]$. And this in turn implies that the orthonormal matrix $X’=V’\cdot U^T$ has now determinant $+1$!

4.4. Algorithm

The steps for Arun’s method are as follows:

- Compute the centroids of the world and camera points: $$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} \bar{P} &= \frac{1}{N}\sum_{i=1}^N P_i \\ \bar{P’} &= \frac{1}{N}\sum_{i=1}^N P_i' \end{split} \end{equation} $$

- Compute the centered points: $$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} Q_i &= P_i - \bar{P} \\ Q_i’ &= P_i’ - \bar{P’} \end{split} \end{equation} $$

- Compute the matrix $H$: $$ \begin{equation} H = \sum_{i=1}^N Q_iQ_i’^T \end{equation} $$

- Compute the SVD decomposition of $H$: $$ \begin{equation} H = U\cdot D\cdot V^T \end{equation} $$ where $V=[v_1, v_2, v_3]$.

- Compute the orthonormal matrix $X$: $$ \begin{equation} X = V\cdot U^T \end{equation} $$

- Inspect the determinant of $X$

- If $\text{det}(X) = 1$, then $R’ = X$.

- If $\text{det}(X) = -1$, then $R’ = [v_1, v_2, -v_3]\cdot U^T$.

- Compute the translation vector $T$: $$ \begin{equation} T = \bar{P’} - R’\cdot\bar{P} \end{equation} $$

5. Example

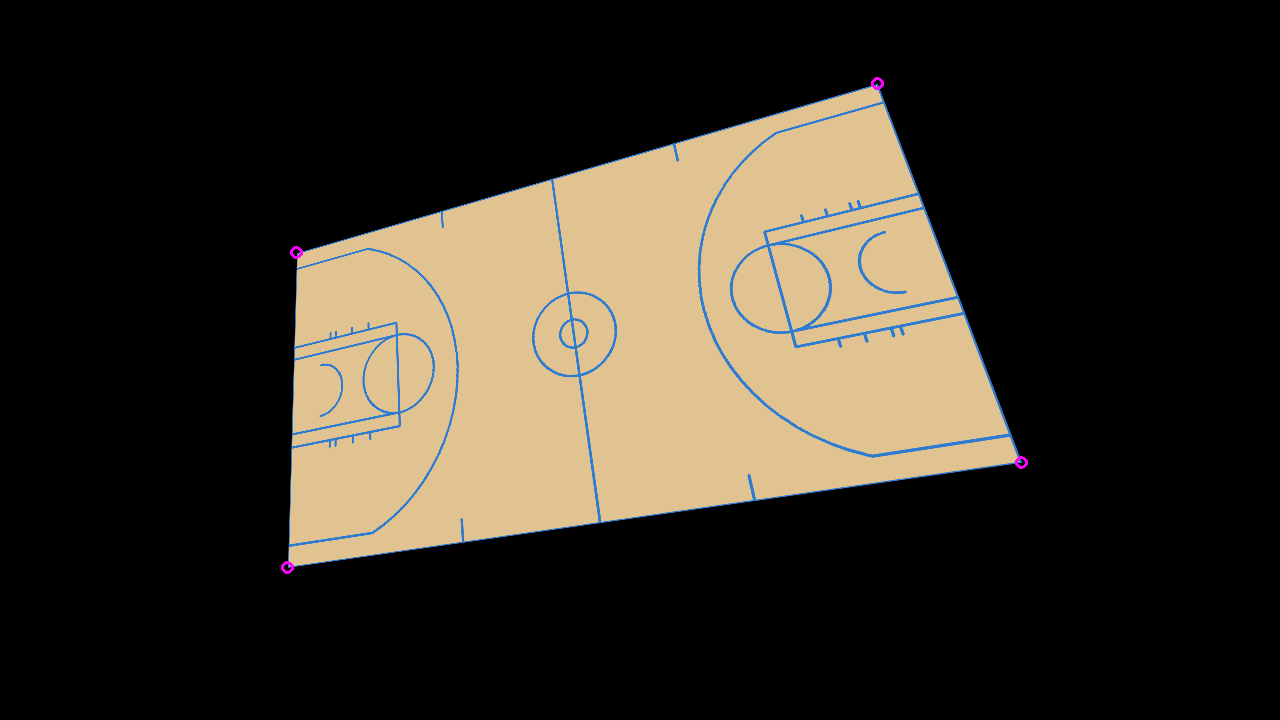

Let us follow up on our first scenario for the camera calibration article. We started from the synthetic image displayed below, which was generated with the following camera parameters:

$$ \begin{equation} \begin{split} f &= 350 \text{ pixels} \\ t_x &= -5 \text{ pixels} \\ t_y &= 5 \text{ pixels} \\ t_z &= 15 \text{ pixels} \\ \theta_x &= -170 \degree \\ \theta_y &= 10 \degree \\ \theta_z &= 170 \degree \end{split} \end{equation} $$

We already saw we can retrieve the focal length from the two vanishing points, so let us assume it is known. We can now retrieve the camera pose from 4 non-collinear points, which in our case correspond to the corners of the basketball court. We know their coordinates in the world coordinate system given the court dimensions, and we can identify their image coordinates in the synthetic image.

In order to estimate the camera pose, we can pick 3 points to obtain the candidates based on the P3P algorithm described above. Then, we can select our final guess by choosing the candidate that minimizes the reprojection error in the remaining point, which gives us the values we expect.

Note: you can give it a try by simply running this script. In order to do so, just install the repository (poetry install) and then run

poetry run python -m projective_geometry camera-pose-from-four-points-demo

6. Conclusion

In this article, we have seen how to retrieve the camera pose from 3D points and their corresponding 2D projections. We have covered:

- We have illustrated geometrically how many points are needed to remove the degrees of freedom.

- We have explained Arun’s method to find the rigid transform that aligns the world points to the camera points.

- We have introduced Grunert’s algorithm to estimate the camera pose from 3 point correspondences (P3P problem).

- We have detailed how to handle both the noiseless and noisy scenarios.

- We have illustrated how the ambiguity that leads to four valid solutions in the P3P problem arises.

- We have illustrated with a practical example how to retrieve the camera pose from 4 non-collinear points.

7. References

- Richard Hartley and Andrew Zisserman (2000), Multiple View Geometry in Computer Vision, Cambridge University Press.

- Stefen Lavalle, Lecture on “Perspective n-point problem”: YouTube

- Huang, T. S. et. al. (1986). “Least-squares estimation of motion parameters from 3-D point correspondences”, Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Vol. 10.

- K. S. Arun et. al. (1987) “Least-Squares Fitting of Two 3-D Point Sets”, IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, vol. PAMI-9, no. 5, pp. 698-700.

- Cyrill Stachniss, Lecture on “Projective 3-Point Algorithm using Grunert’s Method”: YouTube and slides

- Jingnan Shi, “Arun’s Method for 3D Registration”

- Jingnan Shi, “Perspective-n-Point: P3P”

- OpenCV Libary: Basic concepts of the homography explained with code

- Law of Cosines: Wikipedia

- J. A. Grunert (1841) “Das Pothenotische Problem in erweiterter Gestalt nebst Über seine Anwendungen in der Geodäsie", Grunerts Archiv für Mathematik und Physik, Band 1, pp. 238–248.

- Trace of a matrix: Wikipedia

- Singular Value Decomposition: Wikipedia

- Cauchy-Schwarz inequality: Wikipedia